| “Indian elites show little evidence of having thought coherently and systematically about strategy.” — George Tanham |

One of the manifestations of changing Chinese doctrine is the introduction of a new cliché in the lexicon of Chinese think tanks, namely ‘Grand Periphery Military Strategy’. The Chinese move to expand high speed rail networks and equipping over 1,000 railway stations with military transport facilities points towards concrete military steps being taken in this regard. This will ensure rapid offensive deployment as required to the many and diverse border regions of China. Thus proactive military actions along several theatres will be a possibility. The excellent fast rail network to Tibet is a pre-eminent example of adherence to the Grand Peripheral Military Strategy of China and further its connectivity to Nepal and the Chumbi Valley is being planned in the near future. China’s nuclear weapons–cum-missiles nexus with its client state, Pakistan and modernising the Pakistani Armed Forces is singularly aimed against India. For China, Pakistan is a low-cost guarantor of security against India and China now a high value guarantor of security for Pakistan against India. Since the last two years or so, the Chinese footprint in the disputed POK region is growing.

|

Click to enlarge |

| This article is published with the kind permission of “Defence and Security Alert (DSA) Magazine” New Delhi-India |

|

|

Here you can find more information about:

|

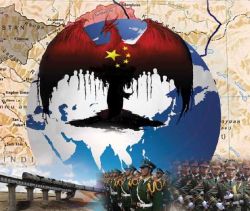

Nearly 200 years back, Napoleon had prophetically stated that “let China sleep, for when she wakes, the world will tremble.” Today, China is the world’s fastest growing economy, with the largest, if not the most powerful, Armed Forces in the world and foreign reserves at US$ 3.2 trillion — far exceeding even those of the sole super power — the now economically weary and strategically fatigued US, all translating into China’s ever growing global clout.

China’s burgeoning financial and consequently its military might continues to be on a rapid upswing propelled by its ancient civilisational wisdom of realpolitik embellished by a strategic vision and nationalistic ambitions which are distinctly unparalleled. That China will be a super power by 2025, if not earlier, will be understating a stark reality. If the 21st century has to be an Asian century, as repeatedly proclaimed by many geo-political luminaries, China leads the way well ahead of the other players on the scene including India, Japan, S. Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia etc. China is usually bracketed with India as the lead players in emerging Asia but India merely plods along never having risen yet to its true potential because of its inner contradictions. That China sees India as its main rival, globally, regionally, economically and militarily, makes the growing asymmetric chasm between the two neighbours and Asian giants a serious cause of worry, in the foreseeable future, for India.

As China builds-up a formidable military machine, it is conscious of inculcating a responsible image for world consumption in keeping with its growing global status. Thus China has been since 1998, issuing every two years White Papers on national defence with the latest in the series issued late last year — on China’s National Defence in 2010. This paper comprehensively covers all macro-issues concerning national defence.

China’s stated aim in its aforesaid White Paper is the pursuit of a defence policy which ensures a stable security environment and permits the development of its economy and the modernisation of its military. Importantly, it relies on military power as a guarantor of China’s strategic autonomy and aims to ensure that China continues to enjoy unrestricted access to critical strategic resources like oil and natural gas. China, further stresses that its national defence policy is primarily defensive in nature and that China launches counter-attacks only in self-defence. China further claims that it “plays an active part in maintaining global and regional peace and stability.” It continues to proclaim, that it follows a “no first use” nuclear doctrine and is a responsible nuclear and space power.

Most strategic analysts the world over and particularly its neighbours, however, dismiss China’s noble-sounding rhetoric as nothing more than a public-relations exercise as China’s actions in the past few years, all across Asia, have been anything but contributing to regional harmony. On the contrary, China is well on the way to have become a regional hegemon as many of its actions clearly show especially the turbulence it has created by its muscle-flexing in the many waterways which lap the Chinese coastline whether it is the South China Sea or the East China Sea including its many unfair claims on various island territories in South-east Asia.

China’s nuclear weapons-cum-missiles nexus with its client state, Pakistan and modernising the Pakistani Armed Forces is singularly aimed against India. For China, Pakistan is a low-cost guarantor of security against India and China now a high value guarantor of security for Pakistan against India. Since the last two years or so, the Chinese footprint in the disputed POK region is growing under the garb of engineer personnel being stationed in the region (approximately 7,000 to 10,000 personnel already there) and reports suggest that POK may be leased to China for 50 years or so

Grand periphery military strategy

One of the manifestations of changing Chinese doctrine is the introduction of a new cliché in the lexicon of Chinese think tanks, namely ‘Grand Periphery Military Strategy’. This presupposes the fact that the People’s Liberation Army, surprisingly to many outsiders, lacked the capability of defending its ‘far flung borders.’ Now other Chinese military thinkers are reinforcing this newer strategy to be adopted in the face of rapidly changing geopolitical dynamics in South Asia, Central Asia, South-east Asia and North-east Asia. The Chinese move to expand high speed rail networks and equipping over 1,000 railway stations with military transport facilities points towards concrete military steps being taken in this regard. This will ensure rapid offensive deployment as required to the many and diverse border regions of China. Thus proactive military actions along several theatres will be a possibility. The excellent fast rail network to Tibet is a pre-eminent example of adherence to the Grand Peripheral Military Strategy of China and further its connectivity to Nepal and the Chumbi Valley is being planned in the near future. In addition, the rail link being conceptualised along the Karakoram Highway linking Xinjiang, through the disputed territory of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, to the warm water port of Gwadar in Balochistan along the Makran Coast is another example of Chinese strategic determination to extend its influence beyond its peripheries and dominate regions well away from its boundaries.

As one of the signatories of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific sponsored 81,000 km long Trans-Asian Railway, China has come out with a plan to build high-speed rails to Laos, Singapore, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar along its south-east periphery. It has also got the signal to construct the China-Iran rail that will pass through the Central Asian countries of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan.

Michael Caine and Ashley Tellis of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in their seminal work, Interpreting China’s Grand Strategy: Past, Present and Future, have opined that “the continued increase in China’s relative economic and military capabilities, combined with its growing maritime strategic orientation, if sustained over many years, will almost certainly produce both a re-definition of Beijing strategic interests … that directly or indirectly challenge many of the existing equities.”

von

von