The Indian Navy has been very fortunate to have had visionary leaders. From a minor littoral force of hand-me-down frigates, sloops and craft at independence, the Navy has now emerged as the fifth largest naval power. However in view of the daunting challenges we face we need to do a lot more and ensure this is actualised in an operationally viable time frame. A brilliant and very well informed article on the Force Structuring needs of the Indian Navy. This article conducts a top level gap analysis between requirements and possessions and recommends an action plan to transform the Indian Navy into a force of the future. The writer addresses the major slippages in delivery schedules by our DPSUs and response options that ensure that the Indian Navy does not get into a situation of “too little too late”. Building the 2020 Navy may require some prompt and focused course corrections and re-alignment with the forecast operational scenario of 2022 and beyond.

This article is published with the kind permission of “Defence and Security Alert (DSA) Magazine” New Delhi-India

The Indian Navy has been very fortunate to have had visionary leaders. From a minor littoral force of hand-me-down frigates, sloops and craft at independence, the Navy has now emerged as the fifth largest naval power. This journey has been neither smooth nor easy. The tenacity of purpose and the overall corporate conviction that the charted path of force development would be mainly through indigenous capacity has not wavered, is a clear testimony to the navy’s sound leadership and rank and file consensus on its identity and self belief.

The Indian Navy has long prided itself to be a builder’s Navy. It has been the pioneering service promoting indigenous industry to deliver it the finest ships in the region. Integrating cutting edge weapons, sensors and sophisticated communications with advanced propulsion and power packages from diverse sources to make state-of-the-art ships designed by the Navy is a splendid achievement and the Indian Navy can be justly proud of this heritage. However, doggedly pursuing an indigenous only agenda at the cost of major time over runs is risky.

Though self reliance must indeed be the final objective but that does not mean that every item of a system is sourced only from indigenous vendors. Self reliance, in today’s context, means a mixture of global buy and localised “buy or make” decisions that synergise the competitive advantage of each participating vendor for the common benefit of reduced costs, faster deliveries and most importantly, superior quality and system performance.

|

| Click to enlarge |

The modernisation challenge

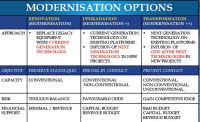

Much has been debated about modernisation and transformation of the Indian Navy. It is therefore important to develop a common understanding of modernisation. A model that has been developed by the writer suggests that modernisation can be visualised as a three tier activity as summarised in Figure above. The Navy has to clearly balance the three tier options in the light of the complexities and procedural requirements of the Defence Procurement Procedure.

Ships and submarines

Naval force level requirements, expressed as a capability statement, has been defined in terms of a Bottom Up-Top Down capability centric perspective plan that defines the platforms that the Indian Navy would require to fulfil its missions until 2022 and the associated organisation that would support it. The Indian Coast Guard has also drawn up a plan envisaging tripling force levels in a decade. Not surprisingly the foremost mission is to combine forces to win decisively in war and ensure adherence to the constabulary and custom laws of the state. However, conflicts are not always won by force alone but paradoxically force level disparities set the stage for conflict.

The Indian Navy has long prided itself to be a builder’s Navy. It has been the pioneering service promoting indigenous industry to deliver it the finest ships in the region. Integrating cutting edge weapons, sensors and sophisticated communications with advanced propulsion and power packages from diverse sources to make state-of-the-art ships designed by the Navy is a splendid achievement and the Indian Navy can be justly proud of this heritage. However, doggedly pursuing an indigenous only agenda at the cost of major time overruns is risky

The challenge for force level planning experts has always remained the uncertainties of the future strategic environment; the technological advances that could change the nature of warfare at sea; and, its consequent implications on structure and composition. First, there is no agreement on what the next war might look like, although China by all accounts would definitely constitute the main opposition to Indian interests in the region. Secondly, out of area contingencies in support of national policy and protection of Indian interest and assets — rapidly diversifying and distributed across the world — is a new phenomenon posing additional challenges to force planning. Thirdly, the perennial debate between the submarine arm and the surface Navy on whether the future lies in submarines or aircraft carriers has to be addressed. Within submarines also, the merits of conventional versus nuclear-powered submarines are still debated and within the aircraft carrier constituency the size and type are always a source of controversy. Finally, sub-regional conflicts that may arise out of 26/11 scenarios and boundary disputes cannot be wished away. Hence, conceptualising a force for the future is truly a challenge since acquisition decisions taken and commitments made cannot be easily reversed.

Force levels have essentially two components viz. force structuring and force composition. In all force structuring decisions the key element is of budgetary provisions and indigenous capability.

Basic principles of force structuring have remained steadfast over the last 60 years. The abiding constants have been the need for a two Carrier Battle Group (CBG), Local Naval Defence (LND) forces for the major naval bases, a well defined submarine force, shore-based long range anti-submarine and patrol aircraft and ship-borne integral aircraft / helicopters. This would mean a surface fleet of three aircraft carriers, about 40–42 frigates and destroyers, four afloat support ships, 80–100 minor LND forces and about 24 submarines. Estimates on requirements of nuclear submarines vary. In addition, force projection would require commensurate amphibious ships of the Landing Platform Dock (LPD) supported with island hopping Landing Craft.

The Navy and increasingly the Coast Guard, true to its character of being a builder’s force, has sourced these platforms to the extent feasible from Indian shipbuilders which have so far been predominantly DPSUs. This is a fatal mistake. If force levels and systems cannot be procured in some reasonable time frame the Navy must find wisdom in its own advice to its Captains — “Swallow your pride, take a tug, save the ship’s side”. Whether the time has come to swallow pride and source from outside only a capability gap analysis will reveal. Deliveries are faster, quality is superior and costs are lesser. The three Talwar Class frigates, under procurement from Yantar Shipyard, Russia at a total cost of Rs 5,400 crore have been made available at only about 40 per cent of the cost of the three P 17s being built at MDL for Rs 8,800 crore and with equal if not better capability. These three ships would be inducted in five years whilst domestic shipyards, on their own, may possibly deliver them over not less than 10–13 years. That capacity building is more important than local sourcing is evident from the fact that even Russia is procuring the Mistral Class Landing Ship Docks (LPD) and building additional ships in technical partnership with France.

So far as force composition is concerned a faithful balance needs to be struck between littoral and open seas requirements within the likely budgetary support that may be anticipated. This is not a difficult task. Allowing for an 8 per cent growth in GDP, an allocation of about 1.8 per cent towards defence expenditure of which about 17 per cent would be the Navy’s share and finally a mix of 60 per cent towards capital and balance 40 per cent towards revenue will give a fair idea of the anticipated budgetary support. However, creating the balance is a very tricky issue and to have it perfect is a tall order for any force planner. Augmentation in force levels and technology to hedge against all forms of conflict in open sea and provide the teeth to aggressive diplomacy is a given. Nevertheless, the first requirement would be to secure the maritime frontiers at the coastline and in the islands and offshore structure holdings of India. This would require that Indian maritime forces are not only modern but are also of contemporary relevance to the Indian state. Lofty declarations of power projection may be music to a sailor’s ear but coastal surveillance and protection from wanton acts of violence is the citizen’s first priority.

For a three carrier navy in service by 2022 it is logical that the supporting ships — 24 frigates and destroyers — should be available by then. In addition, six to eight destroyers and frigates are required in any operational environment for Convoy protection operations and littoral warfare requirements. Considering even 30 per cent of these forces are under refit / maintenance the total requirement works out to 40–42 destroyers and frigates. Against this requirement about six frigates and five destroyers would have reached the end of their already much extended service life by 2022. Five frigates and three destroyers are under construction which would enter service by 2016. Seven frigates and four destroyers have been approved by DAC for induction by 2022. The net accretion would, therefore, be only seven frigates and two destroyers which would at best provide a force level of 29 frigates and destroyers. Therefore, the navy would still require another 11–13 frigates and destroyers provided the existing orders are delivered on time. The net deficiency that needs corrective action now is for a capability gap of about 4–5 destroyers and 7–8 frigates. In addition, about 6–8 corvettes would be required for Local Naval Defence (LND) functions. Considering that the DPSU shipyards are already fully booked to capacity the gap of 11–13 destroyers and frigates and 6–8 corvettes must be bridged by Indian Private Sector Shipyards as a Buy and Make Indian project with some strategic imports. One option would be to build another 8 frigates of the proven Talwar Class in India as a collaborative venture between an Indian Shipyard and Yantar Shipyard, Kaliningrad.

von

von