Again, credible nuclear deterrence is firmly provided by ship borne Anti Ballistic Missile Defence systems. The recent success of the Advanced Air Defence Missile programme of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) augurs well for the Navy. Future Indian Destroyers, quite like the Arliegh Burke, Kongo or KDX-III all of which have the Aegis System, should be equipped with the indigenous Advanced Air Defence System. At a minimum, this would require a Ballistic Missile Defence Fleet of 6 Destroyers.

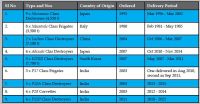

The P75 project for the indigenous construction of DCNS designed Scorpene submarines required that first delivery commences in 2012 and the balance five submarines delivered at one-year intervals to complete by December 2017. Now, the first Scorpene will only be ready in August 2015 and MDL will deliver the balance five by May 2019. The cost overrun is about Rs 4,700 crore. For the second line of submarines, Project P75I, the RFI was issued in September 2010 and the global firms that have responded to it are Russian Rosoboronexport, French DCNS / Armaris, German HDW, Kockums and Spanish Navantia. The initial plan (September 2010) required that three submarines would be made by MDL, one by Hindustan Shipyard Limited (HSL) and Larsen & Toubro and Pipavav Shipyard were to compete for building the balance two submarines. Under the new plan (February 2011) India would order two submarines from a collaborating foreign shipyard and the other four will be built indigenously under transfer of technology with three constructed at MDL and the fourth built at HSL. The point is that the total requirement of the Navy’s submarine fleet is 24. Of this only 6 have been ordered, so far, after more than 8 years of approval of the 30 Year submarine construction Plan which entailed construction of 24 submarines until 2030. Ordering another 6 has already taken more than three years and the production is distributed over three shipyards which, to say the least, is a completely uneconomical model of submarine construction. It would appear that greater economy and efficiency would be obtained had the entire balance of 18 submarines been ordered in one tranche rather than go through this process in small increments of six each every six-seven years. This would require the Navy to freeze the staff requirements for all 18 submarines and then perhaps distributing it in three shipyards may make some sort of economical sense.

|

| Click to enlarge |

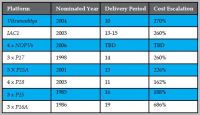

However, the key consideration and the divisive issue that dominates the discussion on categorisation / nomination is of timely induction. The Comptroller and Auditor General has been quite scathing in his comments on the tardiness of the Defence Public Sector Shipyards in delivering on time and cost the ships that the Navy had ordered. It is not as if only the DPSUs are to be blamed for these delays but the malignance is systemic. Cognisance must also be taken of the continued revision of staff requirements to get the best and the latest; and, in the bargain getting too little too late.

|

| Click to enlarge |

World warship building schedules

To put matters in perspective the Table below compares the world standard for warship production of sophisticated warships.

|

| Click to enlarge |

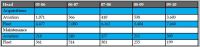

Expenditure towards acquisition and maintenance

In this time, China and our other competitors would march ahead and garner the resources and corner the markets of the world whilst our ships and submarines continue to be built at an elephantine pace. Regrettably, neither China nor other competing nations will allow a strategic ‘time out’ to India for sorting out its warship production schedules in order to build indigenous capabilities. Therefore, nominations to DPSU shipyards must no longer be automatic and a system of synergistic shipbuilding using the capacity in the private shipyard with the expertise in the DPSU shipyards need to be conceived to hasten the shipbuilding programmes. But, Garden Reach Shipbuilders and Engineers have been nominated, as late as October 2011, to build eight 800 Ton Landing Craft (Utility) at a budgeted cost of Rs 2,100 crore with the first LCU to be delivered after 35 months !! In comparison, M/s Fincantieri delivered two 27,500 ton Fleet Tankers in three years. Possibly, the requirements of LCUs are higher and the Navy could have ordered its entire requirement in one tranche on both DPSU and Private shipyards on a competitive basis to reduce costs and improve delivery schedules. On the other hand, a recent RFI for shallow water ASW craft has been categorised under the Buy Indian Route which is a heartening development for Indian shipbuilders.

The second concern is of budgetary support. For the record the five year expenditure on induction and maintenance of fleet and aviation assets is as follows:

Therefore, the Navy has averaged only about Rs 1,200 crore per year for aviation inductions and about Rs 6,200 crore for ship construction over the past few years. Going by public domain data the order book on warships and submarines is about Rs 2,25,000 crore to be inducted by 2022 or nearly Rs 22,500 crore per year. Aviation orders would be worth about Rs 18,000 crore for the ongoing programmes and another Rs 32,000 crore or nearly Rs 5,000 crore per year for new inductions to be achieved by 2022. The obvious conclusion is that unless budgets increase significantly and the capacity to absorb these allocations or the Navy designs and build much cheaper ships and aircraft, the induction targets will not be achievable.

As per media reports only four nuclear submarines may be on order and this itself may take us upto 2022 to induct. Calculations by many experts suggest that the delivery capacity should be at least a minimum of 4 missiles per value target and two per force target

Surveillance systems

Maritime Domain Awareness is a key requirement for successful operations. Sustained and uninterrupted surveillance is the key to maritime domain awareness. This can be achieved through a variety of systems. The first is of course space based satellite surveillance. The Indian Navy is on course to acquire its own communications and surveillance satellite capability with a 1,000 Nm footprint. The second category is airborne surveillance. In this category are the shore based options of Maritime Patrol Aircraft, Aerostats and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and the ship based options of Airborne Early Warning Helicopters and aircraft and VTOL UAVs. A third way is through coastal and offshore surveillance systems consisting of a chain of Radar, AIS and Electro-Optics sensors with a sophisticated command and control software that enables generation of a single composite picture. This segment is with the Coast Guard. Since all of them have inherent advantages and disadvantages therefore an optimal fusion of these three systems is the way ahead. No clear advantage would accrue unless these systems are interconnected and networked to provide differentiated and specific actionable intelligence and presented as a single holistic and composite operational picture.

Surveillance systems for coastal security are under acquisition. A report stated “An indigenously built coastal surveillance system would be deployed in 46 strategic western and eastern locations in the country from this November 2010 to check intrusions from sea and counter such threats, officials said today. Being developed by the Bangalorebased defence PSU Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL), the system includes radars and electro-optic and meteorological sensors and would be mounted on lighthouses or towers.” In this complex system, “The cameras and radars are Israeli,” admit BEL operators … but we are working on developing them indigenously.” It also states that this indigenous system would “give complete operational picture of the sea up to 20 km deep into the sea.” For phase two of the programme the options of better technology such as High Frequency Surface Wave Coastal surveillance Radars or even “X” Band over the Horizon Radars that provide detection and identification ranges in excess of 200 km with reaction time of more than 3 hours combined with Long Range Optronic Sensors of about 50 km range should be inducted.

Aviation

Technology provides the best solution if one is inclined to appreciate it. High Altitude Long Endurance Unmanned Aerials Systems (HALE) with highly sophisticated multifarious payloads supported with multi-spectral data fusion engines is the way forward for oceanic surveillance. The lower capital cost of acquisition, faster deliveries and the near equivalent operating cost must be the dominant consideration for rapid augmentation of surveillance capabilities. These informational inputs must again be dovetailed into a national maritime intelligence grid.

Integrating the HALE with Long Range Maritime (armed) Patrol aircraft would provide an efficiency dividend. The Navy has on order 12 Boeing P8I maritime patrol aircraft. Considering that the generally recognised area of interest of the Indian Navy extends from the East Coast of Africa to the South China Sea this force level is clearly inadequate particularly when nuclear submarines are the dominant threat of the future. These would be delivered by 2015. In addition, an RFI has been issued for another 6 Medium Range Maritime Aircraft and these may only be ordered in 2014–15 going by the normal time lines of procurement. So far as UAVs are concerned the Navy’s present force levels of 8 Searchers and 4 Herons is woefully inadequate to meet even a fraction of the surveillance requirement. The Navy has issued an RFI for Long Range High Altitude UAVs only in December 2010 and induction is therefore clearly a very distant proposition. It is also understood that the services are putting together a single proposal for their combined requirement of Medium Altitude Long Endurance UAVs, though no RFI has been issued as yet. Rotary Wing UAVs for shipborne applications are at the development stage at Hindustan Aeronautics Limited and these may only be inducted no earlier than 2016–17. This is questionable acquisition since Vertical Take Off and Landing UAVs are available using multiple technologies such as Tilt Rotors and Ducted Fan also. Noting that there are now at least four major Indian companies with licences to manufacture UAVs and the total requirement may be in excess of a 100 systems the future induction of UAVs must be through the Buy and Make Indian procedure.

The other area of interest is Seaplanes. This technology has been resurrected with several manufacturers across the world notably in Canada, Germany, Japan and Russia. Seaplanes can provide much needed island support and offshore assets protection, surveillance, long range SAR and CASEVAC, ultra long range fleet logistic support, long range Visit Board Search and Seizure (VBSS) Operations, Humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations, countering small arms and drugs trafficking, human migration, poaching, toxic cargo dumping etc. Unlike conventional helicopters and aircraft seaplanes can land at the location and enforce the will or the law of the country. It is worth noting that Iran already has a strong flying boat squadron of ten crafts. In India, whilst an RFI has been issued for induction of seaplanes the difficulty would be to avoid a single vendor situation. Assuming a Maintenance Reserve of 20 per cent, a Strike Off and Wastage Reserve for a 15 year period as 20 per cent and an assured ability to launch two simultaneous missions from the four coastal commands, 12 operational seaplanes and two training seaplanes would be required. These must be built in India and taken up as a Buy and Make Indian or as Buy Global acquisition. However, since the substance of the seaplanes are its engines it may not be possible to achieve 50 per cent indigenous content. Seaplanes also have civil applications and thus a national capability can be created in niche sector.

However, the key consideration and the divisive issue that dominates the discussion on categorisation / nomination is of timely induction. The Comptroller and Auditor General has been quite scathing in his comments on the tardiness of the Defence Public Sector Shipyards in delivering on time and cost the ships that the Navy had ordered

So far as integral aviation assets are concerned the key determinant must be the future of the Fleet Carrier. The present capability is to be able to work within a 200 Nm bubble and going into the future the bubble should grow to a sanitised space of about 350 Nm. For this the requirement would be for “medium” fighters of the Mig 29K profile or better. With a Combat Air Patrol of four fighters and a turn-around time of 90 minutes, detailed calculations aside, the minimum force level would be two and half fighter squadrons (40 aircraft). In addition, two squadrons of Multi-Role Helicopters, one flight of HALE Early Warning UAVs, one flight of loitering missiles and one flight of communication and utility helicopters should be the minimum embarked Air Group for the future carrier to be considered a potent force.

Both the Sea king and the Chetak helicopters are due for replacement. A case for 16 Multi-Role Helicopters (MRH) and an RFI for Chetak replacement is under process. Another RFP for 91 Naval Multi-Role Helicopters is awaiting approval. The requirements for these helicopters are in the range of 80–100 MRH and about 70–90 twin engine utility helicopters. The Navy could have consolidated its total requirement of MRH instead of inducting in a piecemeal manner. Both these inductions, had they been taken up as bulk acquisitions, could have been through the Buy and Make Indian Route and thus help develop a national competency in helicopter manufacturing. Be that as it may, the option clause (8 MRH) and the repeat order option (16 MRH) should be availed so that induction can reach 40 MRH without retendering. Similarly, Coast Guard requirements for utility helicopters can also be merged to make a very attractive proposition for foreign OEMs to establish manufacturing facilities in India. Even now, further inductions should be explored under the Buy and Make Indian category to help build an alternate to HAL for indigenous manufacture of helicopters. However, licenced production must be taboo and the business model should be developed by the Indian and foreign OEMs on the basis of co design, co-development and co-production as partners not as licenced producers. No OEM will ever transfer enough know-how to its licenced production partner for fear it may become its competitor and therefore Joint Ventures and profit sharing collaborations is the way to go in the future.

von

von